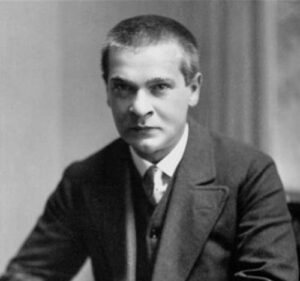

Georg Trakl

Dream and Derangement (eBook)

Selected Poems

Translated by Lucia C. Getsi

Available for Pre-Order

This book will be available on October 22, 2016.

$13.95

Order Now

THE POETRY OF GEORG TRAKL

By Lucia C. Getsi

By Lucia C. Getsi

For Georg Trakl the process of poetic creation is dialectical; it functions in terms of dualities and opposites. Poetic creation springs from the awareness of the schism between the aesthetic “I” and all that is not the “I,” between self and “other.” In Trakl’s early poetry this rupture and the resulting tensions is anifested as the one common to most Western cultures, between the perceiving “I” and the external world of objects. However, in Trakl’s mature poetry the tension be- tween external and internal reality becomes so tightly knit that landscapes flow into inscapes; like images in a dream, Trakl’s images in the mature poetry are already one step removed from the external world from which they sprang. Everything is drawn inward in an expression of a particular intensity of atmosphere in which the poet finds himself.

The self becomes a multiplicity of selves and is dispersed into all its various component selves. However, as if in a dream, the dream eye, or the controlling poetic consciousness, looks on from a distant level of being and receives the essential tone of the drama enacted before it. In this manner, Trakl could in his poems simultaneously be the murderer (or that violent aspect of self which over- whelms the external object and destroys it) and the murderer’s victim, himself as well as his brother, and he could become his sister or the reverse. And just as dreams have an inner coherence, not of logic, but of mood and tone, so do Trakl’s poems.

All stages of emotion, all moods and tones of feeling are objectified into images. These images function as metaphors which reveal the essence of one self from the poet’s multiplicity of selves and also the particular tone of the situation in which this component personality finds itself. Even though Trakl wrote out the personal “I” from his mature poetry, substituting imagistic disguises like “the lonely man” or “a dead thing,” Trakl’s vision, and Trakl was a visionary in the full sense of the word, is him- self; or rather, his inner essential selves.

The way leading into Trakl’s vision is composed of his images, most of which recur again and again, although their meanings are altered, deepened and clarified by the contexts of the poems in which they appear. It is as if Trakl were attempting to write just one poem out of the many: the poem of himself, the poem which would be the complete vision in which all aspects of his personality would be brought into harmony and in which all images would form a composite union. However, this ultimate vision of harmony was never articulated, probably never glimpsed.

Images of decay and disintegration are by far the most pervasive, bringing corresponding moods of anguish and despair. Love, light, joy, when they occur, do so only in the midst of these images, and are usually symbolized by images of the sister, the brother, the child, or by images which represent the poet as a child. These human type images are rarely spoken of in human terms: the sister is a “blue deer,” or a “shape made of moon”; the brother, “joy in the rose-tinged wind, the brother’s gentle song on an evening hill.”

In fact, there are very few real people in Trakl’s work, and none whatsoever in his later poems. There are only shapes, figures, skeletons, phantoms, and those who are as yet unborn. These apparitions are generally in motion-when motion ceases, the effect is never one of tranquility, but of instant terror or dread or despair. This dialectical motion or rhythm between the images is what gives the poems unity, both within them- selves and in terms of each other.

Trakl’s phantom-like images, extensions of the poet’s own divided personality, move in many instances from a containment within the nature images which comprise Trakl’s inscapes toward a fusion with an essential aspect of the poet’s being. But the mergence of selves can rarely ever be maintained, and thus the phantoms are dispersed outward to be again fused with the nature images of the inscape. In the prose poem “Revelation and Decline” the earth vomits up “a child’s body, a shape of moonlight, which slowly stepped from … (the poet’s) shadow, plunged with shattered arms down a stone cataract-flakes of snow.”

The child’s body is one of the many images Trakl uses as a metaphor for his own lost childhood, for imagination, innocence and creativity. This phantom-like image of the child comes from within the earth of the inscape, this earth being a metaphor for the shadow of the poet’s self, for the ground of being and the unconscious past, and moves into fusion with an aspect of the poet’s being, that particular aspect which is a severed extension in the present of the child- image in the past. But this fusion cannot be maintained. The child- image plunges again into a fusion with nature, becomes “flakes of snow,” an image of dispersal, even of death. And this suggests the inability to contain the pure creativity which the child at one time held intact.

These images of dispersal, of phantom-like extensions of the poet undergoing a metamorphosis into natural imagery and then splintering, occur repeatedly. This presents an overwhelming problem for the poet; for each time an aspect of the poet’s self moves toward fusion with an internalized object, that object, or image, not only is immediately separated from the self, but is dispersed, splintered and changed in form, making the next attempt at union even more diff cult.

And from this comes the despair so evident in Trakl’s poetry. Dispersal images suggest a kind of death, an inability to recapture for eternity a part of the poet’s self. The image, or internalized object, which is an essential extension of self, is changed with each union, and this process is a continuous chain of alterations. At another point the same prose poem quoted from above reads: “more and more blackly depression clouds my severed head, horrible flashes of lightning terrify the nocturnal spirit – your hands rend my breathless breast.”

The flashes of lightning are the hands. And again: “A black cloud encircled my head, crystal tears of damned angels. Blood ran softly from the silver wound of my sister and a fiery rain fell upon me.” The crystal tears, a human characteristic as well as an image of transition, disperse from the natural image of the black cloud, and blood becomes a fiery rain. All of these images are metaphors which move toward and merge with an essential aspect of Trakl; the movement is from solidified, contained images to ones of dispersal and death.

And although this movement suggests despair, at the same time it suggests a kind of paradoxical affirmation. Even though images, internalized objects, may change, disperse, fade or momentarily disappear, they still have an existence in the poet’s mind, an existence which is transmuted into other types of existence with which the poet may again seek union. Because nothing ever vanishes from the inscape, even though it may be changed in form, a harmony be- tween disparate elements of self continues to remain in the realm of possibility.

Because all the phantoms in Trakl’s poetry are internalized extensions or objectifications of essences in the poet’s own personality, any love that is manifest in the poetry is a love of and for the self. Thus we find no real love poems, or poems in which the poet seeks a union with an external object and allows that object to speak for itself through the medium of his being. The closest Trakl’s poems ever come to love is when the sister image occurs. Whether or not the poems refer to Trakl’s own sister Margarete is beside the point, for in the poems the sister image becomes a feminine extension of part of the poet’s personality. This is nowhere more evident than in the last section of “Dream and Derangement”:

A purple cloud darkened his head and in silence he fell upon his own image and blood, a face filled with moon; like a rock he sank into void, as his sister, young dying boy, appeared in a broken mirror. And night devoured the race of the damned.

Once again the images are in movement. Purple is the symbolic color which suggests memory and, by extension, suffering. Thus within a framework of memory, of the past, the poem’s speaker momentarily merges with the sister-image, his own “image and blood, a face filled with moon,” with the feminine projection of himself. But the union cannot be maintained. The poet sinks into void, falls through the harmony of selves he has achieved, shattering the mirror of consciousness. The sister falls back into the shadow, into the timeless, un- conscious id; and her image, and simultaneously the image of the child poet, the “dying boy,” is dispersed, and only the fragmented reflection of the image remains within the boundaries of the present, momentary experience.

Trakl’s treatment of the sister image in his poems is ambiguous. At times this image brings about a terrible guilt, a destruction, or a total engulfment in darkness, in “Umnachtung,” as in the above quoted poem. In the same poem while the poem’s speaker is thinking of passionate things (“his thoughts afire”) the sister image appears as a “flaming demon in a coat of hair… When they awoke, the stars died above their heads.” Then, probably because of the union implied by the last sentence, images of guilt follow:

When each destiny is fulfilled in defiled chambers, death enters the house with mildewed tread… O the terror when each knows his guilt, walks pathways of thorns. Then in the thorn bush he found the white form’ of the child, bleeding for the coat of its bridegroom. But he stood before her mute and sorrowful, buried in his hair of steel.

For Trakl the thorn is a symbol of guilt, and many times the sister image occurs within this context of symbolic guilt. This is understandable if one keeps in mind that the sister image is but an extension of an essential aspect of the poet, and that any love union which hap- pens does not arise from a need to give expression to the sister for herself, but rather from a need to obliterate the sister image by over- whelming it, bringing it into a forced union with the poet’s self.

However, there are other poems in which no physical union is implied, and in these the sister image appears in contexts of almost complete, if melancholy, serenity, as in the following section of “Revelation and Decline”: Speechless I lay under old willows and the blue sky arched high above me, full of stars. As I died towards it, gazing, fear and pain died most deeply in me; the blue shadow of the boy arose, radiant in darkness, a gentle song. On lunar wings my sister’s white face rose over green treetops, crystal rocks.

Here the harmony and unity implied in the “crystal rocks” takes place on a plane of the inscape which suggests distance between the “I” and the sister image. The “I” is flowing outward within its essence toward the essence of the object, the “white face” of the sister, in an activity which implies no physical motion. This type of activity, a harmony of essences between the perceived and the perceiver, in which a distance is always maintained between them produces the lyrical beauty and the serenity in this particular passage.

One of Trakl’s most tranquil poems is in itself a hymn entitled “To the Sister.” Although God has “twisted” her eyelids, has distorted her vision and has therefore, by implication, caused her madness, perhaps even because He has done this to her, she is a “child of the Passion,” and “at night stars seek the arch of her brow.” In this poem we can see the possibility of a redemptive function in the sister-image. As a “child of the Passion” she IS born within sacrifice, born from the sacrifice of the poet’s self as well as from the sacrifice of herself in becoming an extension of the poet. She is his creation, and is therefore the symbolic embodiment of his sacrifice.

She must, in order to yield a sense of tranquility, remain an extension of the “I.” The “I” must remain fragmented, objectified into internalized objects, must continue to be sacrificed in order for the sister, functioning almost like a “Magna Mater” figure, to lead it to rebirth into a higher innocence. The “I” cannot return to the innocence of the primordial child; thus the guilt and damnation inherent in the attempt at a complete, almost physical, union with the sister. The poet must achieve innocence, creativity on a higher plane, even if it is a plane of inner reality cut off completely from the external world.

Thus the sister-image brings guilt and violent destruction only when she, and her madness, is raped, is overwhelmed by a forced union with the poet’s own. Her madness, the feminine projection of the poet’s, is a madness in which creative energy and beauty are possible. The poet’s own madness is filled with despair, with “Umnachtung,” the decline of reason, insanity which lives in its own private, dark vision. When the sister image comes into direct contact with an aspect of the poet’s being, the result is fear, guilt and damnation.

This type of narcissism, an aesthetic love of self only and not a love of objects for themselves and their essential functions, brings about the guilt. The poet damns himself with each union he forces upon the sister image, for this means death to her existence and to the possibility of a higher form of innocence and creativity which she sustains. The sister image itself does not bring on the damnation; when allowed to remain at an aesthetic distance from the being of the poet, the function of the sister image is redemptive in nature.

The movements, or tension of rhythms, between internalized objects and essential aspects of the poet establish relationships be- tween various levels of inner reality. The tension of rhythms is concerned with the dynamic energy an object or form possesses and which it transmutes to another object or form on a different level of reality, but whose psychic energy proceeds from an essence which is the same as, or similar to, its own. When one of the poet’s essential selves con- fronts an internalized image or extension of self, the image and its corresponding plane of reality are usually destroyed through union.

However, this attempt at a union between self and projection of self also works in a different manner; that is, the poet’s essential selves also seek a union of essences instead of a symbolically physical fusion. Instead of drawing the object or form into the self and overwhelming it with his own psychic energy, the poet at times projects psychic energy outward toward the object and its level of inner reality seeking to find a correspondence or rhythm of essences.

When this type of correspondence or tension of rhythm between essences occurs, we find the greatest amount of tranquility, that kind of melancholy serenity contained in “To the Sister,” in each passage which contains the image of the brother, and in the poems which concern Elis or any other “phantom” which suggests the primal child in the poet; in effect, in each poem wherein the tension between the two images suggests or implies an aesthetic distance which is maintained between the two images regardless of their free-flowing, corresponding rhythm of essences. When a tension between images such as this occurs, the concept of time is either suspended or abolished; time undergoes a transmutation into spatial imagery. This suspension of time is basic to the affirmation in Trakl’s poetry.

The entire populace and landscape of the poet’s myth is internalized and abstracted from the material and temporal world where life and death preside. And although death is always in some way present in the poetry, nothing ever dies. Forms change but never disappear. Thus even in the midst of the pervasive scenes of decay, dis integration and death we find shapes and shadows radiant with light, with innocence, even, at times, with joy. When the principle of time is in some manner made momentarily ineffective, the resulting tone is one of affirmation, an affirmation so strong that it can even rise out of resignation, anguish or despair. This type of affirmation rising out of resignation, of praising in the form of lament, can be seen in the poem “In Hellbrunn”:

Again trailing the blue lament of evening,

As if suspended above the hill near the spring pond,

Shadows of those long dead,

Shadows of ecclesiastical princes, noble women;

Already their flowers are blooming, earnest violets

In the evening earth, murmuring of the blue brook’s

Crystal waves. Religiously oak trees bend green

Over neglected paths of the dead,

The golden clouds over the pond.

The tranquil tone in the poem derives from the aesthetic distance maintained between the poet and the “shadows of those long dead.” The aspect of time is suspended throughout the poem; the princes and women are already “long dead.” They have passed beyond that state of existence in which time can dole out death, have moved out of time’s realm. The poet has resigned himself to their death, and because of the corresponding rhythm between the essential energy of the poet and the image of the shadows, a rhythm which sustains the tension between them, the poet has also been momentarily carried beyond time. Time is dissolved into the spatial imagery, or nature imagery, of the inscape where the shadows are contained within the eternal cycles of nature: within “earnest violets,” the “murmuring of the blue brook’s crystal waves,” or within the “golden clouds” reflected in the pond’s surface.

Even in poems filled with the unrelenting anguish and despair found in “Decline,” in which line after line every hope is shattered, the lyrical beauty is usually intensified by the anguish. In “Decline” we are left with the final image of blind men made so helpless by their own self-imposed limits of time and civilization that the only way open to them is to climb through time toward death, when time shall no longer exist. The direction leading to death is the only direction, positive or negative, left to take; death is the only remaining thing that the poem’s speaker can affirm, the only thing which has any possibility of bringing peace or redemption. In this poem, as in all poems in which the brother image occurs, the brother is but an extension of that essence of the poet which corresponds to the primal child and its innocence; as with the sister image, images of the primordial child within the grown poet are treated ambiguously in the poems.

And again like the treatment of the sister image, whether or not the appearance of a child image brings despair or possible redemption lies in whether or not the tension or aesthetic distance is sustained between the image and that essence of the poet which seeks harmony with the image. Images of the child are objectifications of one of the poet’s multiplicity of selves; they are extensions from the poet’s past with which he at times attempts a conscious union that would force the image of himself in the past to also be the poet’s destined image in the future time. In other words, the fixation to the past alienates the poet from the present and causes him to seek his future within the past. When the poet seeks union with the child-image in an attempt to discover his future in a return to the primal child, despair results, because in a union of this sort the tension is destroyed. This type of despair resulting from a loss of tension or aesthetic distance is evident in the following section of “Revelation and Decline”:

… A white voice spoke to me, saying kill yourself. Sighing, the shadow of a young boy arose in me and gazed at me radiantly from crystal eyes, so that I sank down weeping beneath the trees, beneath the mighty arch of the stars. In order for the child image, the “shadow of a young boy,” to bring peace or possible redemption, the poet must kill himself, must symbolically sacrifice himself, or rather the fusion of his essential selves, and allow the image of the child to remain an extension of the self. But the “I” of the poet cannot do this and thus sinks into despair.

However, in other poems the aesthetic distance between the image of the child and the poet is not destroyed, and the result is that kind of resigned affirmation which is found in the Elis poems. Elis is one of the names which Trakl attaches to the child image. In “To the Boy Elis” Elis has already died (“O how long ago have you died”); that is, by becoming an objectification of one of the poet’s selves, Elis has been carried beyond the realm of time into the psychic energy of the poet. Being thus removed from the realm of conscious time, Elis moves eternally through the “night,” or the dark unconsciousness, of the poet, and no forced union between the poet and Elis is implied:

Yet with supple steps you traverse a night

Hung with grapes of richest purple,

And your arms move more beautifully in this blue.

Time has disappeared within that area of unconsciousness which is timeless, into the pure space of a night which can be traversed, which can be adorned with “grapes of richest purple.” And the resulting tone throughout the poem is serenely lyrical and affirmative. Even the “black dew” upon Elis’ temples is made something splendid, because it is the last beauty, the “final gold of dying stars.”

The image of the stars is pervasive in Trakl’s work. Stars function in the poetry as a symbol of destiny, as the object of the process of becoming. In most instances this is a negative function, for the type of destiny which the stars represent is the quest for the future within the past, a return to the primordial child. If the stars fade or die out, as in “To the Boy Elis,” the result, if tension is maintained, is paradoxical affirmation; that is, the possibility of returning to primordial innocence is abolished with the fading of the stars, and the image of the child remains an extension of an essential aspect of the poet. In “Caspar Hauser Song” the function of the star is similar in that it carries a paradoxical affirmation, even though the image of the star does not fade. Caspar Hauser is yet another name which Trakl bestows on the child living in the paradisaical past of the poet.

This paradise is depicted in the first two stanzas of this poem, and the fall from paradise occurs simultaneously with the first desire, with the “gentle flame” God spoke into Caspar Hauser’s heart, which forces him to seek the civilization of men. And this falling from paradise effects a division within Caspar Hauser’s being, a schism which causes Caspar Hauser to develop in two different directions: toward his star and the fulfillment of his primordial innocence, the direction in which “animal and bush” will not let him rest until he has realized their innocence; and also in the direction which would, and does, destroy primordial innocence, in which “house and dusky garden of white men” will give no peace until their victim is as pale and shut away from primal nature as they are. As a result of this split in personality, Caspar Hauser becomes a murderer and the victim of the murder in a kind of self-dictated suicide. Caspar Hauser as primordial child remains “alone with his star” and is the victim of his other self, the murderer.

Yet because the child is killed before it reaches a state of non-innocence, the child image falls beyond death into the shadow or ground of being which is timeless, becomes the “one yet unborn” into the consciousness of the grown-up Caspar Hauser. This image of the “one yet unborn” will remain an extension of that essence or self of Caspar Hauser which corresponds to the essence of the primordial child within him. And because this child image has passed beyond time and death into the timelessness of the inner, unconscious aspect of self, a harmony or union of corresponding essences will always be in the realm of possibility. All images of the murderer, as well as similar images of the hunter and the horseman, function in this manner. They are negative in that they seek a coercive union with, and thus the annihilation of, images of primal innocence. But they are also paradoxically affirmative in that the pursuit and sometimes resulting destruction of these images of innocence have the ultimate effect of allowing these images to remain in the eternity of the poet’s inner reality.

The poem which would ultimately serve to unite all the disparate elements of Trakl’s aesthetic self was never written. All the images which suggest the paradise of pure and natural, creative innocence are internal objectifications of the poet’s self which are cut off from the external world of objects; and from this severance and the type of self love it generates arises the guilt so evident in the poetry.

When the poet seeks to bring these extensions of self, all aspects of his personality, into the composite, conscious and symbolically physical union, which is the ultimate aim of this kind of aesthetic narcissism, damnation and despair result. Yet even within the damnation and the guilt, Trakl’s images are still shadows of a paradise that, lost to external reality as it is, is transformed into psychic, creative energy within the inner reality of the poet’s vision. And within this inner reality and in the midst of terrible disintegration and despair, harmony and even the way leading to a higher plane of innocence and creativity beyond both the primal child and the man are still affirmed possibilities. For Georg Trakl the dialectic of the poetic process was both his damnation and the method of attaining harmony and self-completion. The world of poetry became the only world which could give space back to being; the poem was being’s affirmation.